|

| photo by Larry Litman (all photos except as noted are by Litman) |

Exciting recent news out

of Rome: the opening of a museum dedicated to stolen – and recovered –

works, rather than one-off shows such as those held once in a while in Castel

Sant’Angelo’s exhibition space or the Carabinieri museum, as occurred in 2016.

Now there’s a beautifully

refurbished space that Rome resident Larry Litman (retired AmBrit librarian) recently

visited and writes about here (more on Larry’s bio later in this post).

Before we launch into Larry’s first-hand guide to the new museum and his many photos of the Carabinieris' marvelous finds, we'll explore some of the hot topic news and issues surrounding the museum and the works.

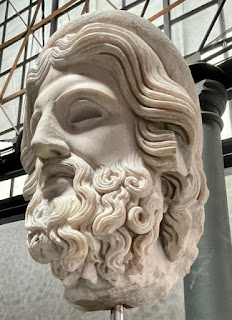

Hardly a week goes by without news of “stolen” artworks being discovered in places far from where they were taken. Just this month, the New York Times reported 27 ancient artifacts, valued at $13 million, were seized from the venerable Metropolitan Museum of Art. Interestingly, it’s the Manhattan District Attorney’s office that seized the items at 3 separate times, including 21 Italian pieces taken from the Met in July, pieces that are similar to the head of Esculapius, below, from the current Rome exhibit. (One has to wonder, as one does these days, why did they have to seize the works? Why didn't the Met willingly turn them over?)

|

| This head of Esculapius, above, copied from a Greek original, is from the late 2nd-3rd century AD and was taken from the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. |

A few days earlier, the FBI Art Crime Team reported in a news release that it had recently returned to Italy a 2000-year-old mosaic. “The enormous work had been cut into 16 pieces and stored in individual pallets in a Los Angeles storage facility since the 1980s. Each pallet weighed between 75 and 200 pounds.”

We, at RST, are familiar with the art recovery section of the Italian national police, the Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, or TPC (Cultural Heritage Protection Squad), but we hadn’t known of the Manhattan DA’s interest in these objects, nor the FBI's – it seems they have enough else going on these days!

|

| Special Agents Elizabeth Rivas and Allen Grove traveled to Italy for the repatriation of the mosaic to its home in Rome - photo from FBI news release. |

|

| Similarly flanking their "prize," the Carabinieri at their 2016 news conference on art (which we attended and covered in a post) they had recovered, in this case a Canaletto, from the 18th century (photo by William Graebner). |

The “recovered” artworks raise multiple issues, including how a country such as Italy or Greece or even Ethiopia (more about Ethiopia in a future post) can conserve, protect, and display these objects. Italy has taken the approach of returning them to the regions from which they came, a somewhat controversial position.

Larry notes “Several years ago I visited Aidone in Sicily to see an amazing

statue of Venus returned from the Getty museums in Los Angeles and a collection of Silver

Plates from the Met. The region built a museum in a redundant convent to house

these items and other artifacts from the area.” The long saga of the Getty's involvement in stolen works, including lawsuits and criminal actions, are well-reported in David Price Williams's 2015 "Looking for Aphrodite." The Getty also helped restore items for the Aidone museum, and put some of the objects on display (this time, on loan) at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, a sort of reciprocity (we were fortunate to see Venus in Los Angeles, before she left for Sicily). So, maybe there’s an advantage

to spreading this “wealth” around. Although New York Times' writer Elizabeth Polvoledo had a different experience from Larry's in the once-Etruscan hub of Cerveteri, near Rome, where the museum did not have the staff to stay open (see caption under Larry's photo of the Etruscan female antefix below).

Journalist and author Sari Gilbert also used a stolen Etruscan vessel as the key to her intriguing murder mystery set in 1980s Rome, "Deadline Rome: the Vatican Kylix," which we reviewed here. As noted above, current, exciting, hot topics involving 2000-year-old art.

This is RST's 4th post from our "man [almost always] on the ground" in Rome, Larry Litman. Larry wrote eloquently in March 2020 about being in Rome under one of the first lockdowns. He gave a virtual tour of the unusual presepi or crèches in Piazza San Pietro (St. Peter’s Square) that year when almost no one was there to see them, and he was one of the first (as he is this time) to see the inside of the Tomb of Augustus, newly opened last year.

Larry is a retired teacher/librarian from Ambrit International School and is active at St. Paul's Within the Walls (the Episcopal Church on via Nazionale). He also volunteers at the Non-Catholic Cemetery.

Rome’s newest museum: The Museum of Rescued Art - by Larry Litman

|

| Entrance (after you've purchased your ticket around the block), still with "Planetario" above the doorway. |

|

| A 2nd century AD copy of a Greek statue of Doriforous by Polyleitos, from the Baths of Caracalla; so presumably it will stay in Rome. |

The Museum of Rescued Art will present changing exhibitions of objects recovered by the Carabinieri unit for the Protection of Cultural Heritage.

For the foreseeable future there will be

enough recovered items to keep the museum going. It’s giving a visible profile

of the Carabinieri unit involved, discouraging theft and encouraging

restitution/return.

This initial exhibition features about 100 objects from more than 200 artifacts, dated from the 6th century BC to the 3rd century AD, stolen over the past 50 years, that were returned to Italy from the United States between December 2021 and June 2022. The New York Times, in a piece about the new museum, called this location a “pit stop,” because all objects at some point will be returned to their places of origin in Italy.

The soaring dome of the Octagonal Hall [photo

at top of post] is an impressive environment for this new Museum of Rescued

Art.

Admission for the National Roman Museum

also allows entrance to the exhibition of recently returned artifacts. (Note:

You must buy the admission ticket at the main museum entrance facing Termini

Station and then walk around the block, through Piazza della Repubblica, to

enter the Museum of Rescued Art.)

Explanatory panels on the display cases

are in Italian and English, identifying the objects in each case as well as presenting a

narrative about the work of the Carabinieri to identify stolen art and

negotiate the return of works from private collectors, museums and galleries

with the cooperation of authorities in the United States.

More photos and descriptions follow.

|

| Ceremonial Kramer with four handles surmounted by red impasto bowls overpainted with white ("white on red"), produced in Northern Lazio. |

|

| Decorated Etruscan terracotta storage vessels. Again, one wonders where these objects will end up. |

|

| Statue of Artemis, 2nd century AD, from the Baths of Caracalla. |

|

| Etruscan olpe (pitcher) made in a Corinthian style with animal friezes, first half, 6th century BC. |

|

| Black and white painted terracotta vessel from the ancient town of Crustumerium, a site now identified about 10 miles north of Rome near Settebagni, 7th century BC. |

|

| Brown cremation urn in the shape of a house with figured decorations (horse, soldier and boat) on the walls and on the lid. 7th century BC. |

|

| Etruscan terracotta votive heads, 8th century BC. |

No comments:

Post a Comment