To dub or not to dub; that is...not a silly question. Italians especially have taught us the value of a dubber (doppiatore, literally a “doubler”), make that “voice actor,” a respected profession in Italy.

The value Italians give to the craft is exhibited by what are known as the “Italian Oscars”—The International Grand Prize of Dubbing, il Gran Premio Internazionale del Doppiaggio. The 14th annual prizes were handed out at the recent March 27 ceremonies. Italians’ attraction to dubbed films was also underscored recently, when the dubbers went on strike for 3 weeks, protesting a contract that expired 12 years ago. As a consequence, no dubbing took place, and no shows were aired dubbed. When, during the strike (it’s now on pause), Sky TV streamed the 7th episode of HBO’s smash hit “The Last of Us” in its original language, English, Italian audiences reportedly were disoriented.

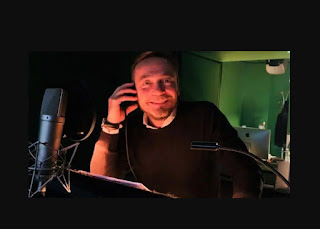

|

| Above, Simone D'Andrea, who won the jury prize for "Best Male Voice" this year for his dubbing of Colin Farrell in "The Banshees of Inishirin." He's also known for anime voicing. |

Unlike most

Italians, Americans generally devalue dubbed films. For those of us who were

introduced to “foreign films” in church basements or tiny art houses, “dubbed”

films were considered vastly inferior to subtitled ones. We might not have

known one word in Swedish, but we considered it critical to hear the sounds of

the original actors in those Ingmar Bergman classics. Were we wrong?

Edward

Lynch, a dual citizen and multi-lingual professor in Rome, who created a

website devoted to films in original language showing in that capital city, seems

to be the perfect person to defend subtitles. But, like us, he’s modified his

views somewhat over the years. “I used to see dubbing as something really bad.

But maybe it’s not all that bad. The problem in Italy was that there wasn’t

much of a choice in the past. All films were dubbed.”

Lynch points to “Parasite,” the 2019 Korean movie that went on to win the Oscar for Best Picture, one of the few foreign films to do so. He saw it with subtitles, and says that by spending time focusing on reading the words, “I think I missed a lot.” He adds, “Even if it’s in a language I don’t know, I want to see it in the original with subtitles. But maybe I’m being too stubborn. I think I would have liked to have seen ‘Parasite’ dubbed.”

Dubbing may

be coming more into its own internationally with streaming. The film that won

this year’s Oscar for Best Foreign Film, Germany’s “All Quiet on the Western

Front,” was offered (on Netflix) in several versions, including a dubbed

English version. A non-German speaker can choose to watch it either dubbed or

subtitled. Streaming at home would seem to encourage this multiplicity of

versions.

At least in

Rome, one also has some of that choice at Director Nanni Moretti’s “Nuovo

Sacher” theater in Trastevere, where the programming alternates showing a film one night dubbed

in Italian and another in “v.o.”, versione originale (original version,

i.e. with subtitles). Lynch asked the Nuovo Sacher box office whether one

version was more popular than the other, and they responded that each attracted

about the same number of viewers. Bear in mind, Nuovo Sacher is essentially an

art house, attracting a clientele that might lean more towards subtitles than would

the general public.

Italians’ attraction to dubbing means that Italy is one of the world’s premier dubbing countries. Along with France and Germany, it historically resisted subtitling on the grounds that dubbing would better promote the country’s native language. A perhaps unintended consequence is that people in Northern European countries (like the Scandinavian ones) speak English more readily, because they’ve been hearing the original more often.

In 2018, 570,000 minutes were dubbed by professionals in Italy, and likely even more are being dubbed today. A 2019 headline in the Hollywood Reporter blared, “Netflix’s Global Reach Sparks Dubbing Debate: ‘The Public Demands It.’” One of their VP’s explained, “People say they prefer the original, but our figures show they watch the dubbed version.” Netflix now works with more than 100 facilities worldwide to meet increasing demand for dubbed content. It has 7 dubbing-approved studios in Italy, 6 of those in Rome.

|

| Proietti, right, who voiced Gandalf (Ian McKellen) in the "Lord of the Rings" series. |

There are

schools and programs in Italy today dedicated to dubbing. It’s considered a

high art form there, equivalent to regular acting. The voice actors, as they

prefer to be called, are famous throughout the country, as the “Italian Oscars”

demonstrate. Roman Gigi Proietti, who died in 2020 at age 80, began as a stage

and film actor, but he was most famous for his voice acting. As with many other

voice actors, Proietti was the voice of multiple stars, among them Robert De

Niro, Sylvester Stallone, Richard Burton, Richard Harris, Dustin Hoffman, Paul

Newman, Charlton Heston and Marlon Brando. When Hoffman, De Niro or Stallone

make new films, Italians will have a tough adjustment to make.

Italians like dubbed films because, says Lynch, “they can recognize all the dubbed voices. It’s something that the Italian audience gets used to, these actors who dub and always dub the same actors.”

|

| Proietti was recently honored with an enormous mural on a wall in the Tufello quarter of Rome, the working class area where he was born and raised. |

It’s hard

not to see those many flyers and ads around Rome that promote dubbing schools. The field generally is referred to as audiovisual translation or AVT, and is popular in all of Europe. Massimo Vizzaccaro is a professor at one of the more illustrious of those

schools (one that doesn’t have to slap paste-ups on telephone poles). The

program at his university is an intensive 12-month Master di Primo Livello

(“Master’s first level”; the full name is Master in traduzione e adattamento

delle opere audiovisivi e multimediali per il doppiaggio e il sottotitolo -

“Master’s in translation and adaptation of audiovisual and multimedia works for

dubbing and subtitling” or Master TEA for short). To apply, one must

have a (minimum) 3-year undergraduate degree.

“It’s a hands-on course,” says Vizzaccaro, “because these students are physically taken into dubbing studios; so they see how you need to work.” It’s the longest standing program of its type in Italy, founded some 20 years ago by Sergio Patou Patucchi, a scholar of the subject who was the voice of, among others, Yogi Bear and his companion Boo-Boo. The program also provides a number of different courses, including Vizzaccaro’s own “British and American Civilizations.” His course is essential, the Roman professor points out, because to be good at their trade, dubbers need to understand the culture that produces the content they are dubbing.

|

| Ferruccio Amendola, left, the "king" of voice actors before his 2001 death, with one of his actors: Sylvester Stallone. |

Schools

notwithstanding, a lot of the business in Italy is passed through the family,

like many other Italian professions (e.g. notaries – a much more important

position there than in the U.S.), Vizzaccaro notes. (“Nepo babies” are also

common in Hollywood, as we know.) Carlo Valli, the voice of Robin Williams

among many others, and Cristina Giachero (voice of Scarlett Johanssen and Laura

Dern among dozens) are the parents of two voice actors, Ruggero and Arturo,

both of whom got their start as voices of children or animated figures (Arturo as the young Andy in “Toy Story”). Ferruccio Amendola, considered the

“king” of voice actors (before his 2001 death, he voiced De Niro, Stallone and

Hoffman), was married to voice actress Rita Savignone (Vanessa Redgrave, Whoopi

Goldberg).

|

| Carlo Valli, right, who was the voice of Robin Williams. |

Dubbing, as

well as subtitling, raises fascinating issues of cultural exchange and

transmission, as does any translation. Decisions have to be made about

everything from titles of films (“Scandalo a Filadelfia” [“Scandal in

Philadelphia”] instead of “Philadelphia Story” [1940]) to names of characters (Rossella

O’Hara instead of Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone with the Wind” [1939]), from

regional accents to puns. Example of the last is how does one differentiate in Italian “where

wolf”/“werewolf” to make a joke make sense in 1974’s “Young Frankenstein”? Apparently that was one of the more successful translations; we've quoted the English and Italian versions at the end of this post.

“Translating”

regional accents into dubbed foreign language versions can be a challenge as

well. According to Vizzaccaro, it's generally not feasible in Italian; the equivalent would be more cultural than regional and might be offensive or perceived as silly. There are attempts to make the transition. In the TV show “The Simpsons,” the Protestant Reverend Lovejoy has a

Southern accent. In Italian, points out Italian language and cultural educator

Valeria Mancuso, his dubber speaks with a Sicilian or Calabrian accent.

Apu, the Indian proprietor of the Kwik-E-Mart in that series, in Italian speaks

with a sing-song cadence and grammatical errors, both indicating he’s an

immigrant.

The dubber also has to provide content that at least minimally resembles the words coming out of the actor’s mouth, basically lip-synching. Except in one anomalous case. Vizzaccaro pointed out Scarlett Johansson was an awards nominee for Best Actress for 2013’s “Her,” in which only her voice is present. In Italy, the dubbed version obviously featured someone else. As a result, Italian audiences had no chance to witness the award-winning performance. We might think it strange to have the same voice coming out of the mouths of Dustin Hoffman and Marlon Brando, but the Italians don’t. The “famous” quality of voice actors may have its counterpart in American animated features that often employ Hollywood stars, like Tom Hanks playing Woody in the “Toy Story” series.

Lynch also points out that some Italian films in the past were dubbed—Italian into Italian—because the dubbers have better voices. Elsa Martinelli won best actress at the 1956 Berlin film festival for her role in Mario Monicelli’s “Donatella,” even though her voice in the film is that of another actress. The Italian Wikipedia lists the doppiatori—there were at least 9—for the film (https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donatella_(film)). This point evokes the transition in American films from silents to talkies, which, it’s generally agreed, ended the career of some of those whose voices didn’t match their screen personas.

The prestige

of dubbing over subtitling is reflected not only in the economic and artistic

commitment Italians have to the craft, but also in some cartoons. We end these

ruminations on dubbing with this reminder of that prestige:

|

| The top figure is labeled "Italian Dubbing" and the bottom, "Subtitled Original" |

Inga: Werewolf!

Frankenstein: Werewolf?

Igor: There

Frankenstein: What?

Igor: There wolf, there castle!

Inga: Lupo ululà

Frankenstein: Lupo ululà?

Igor: Là!

Frankenstein: Cosa?

Igor: Lupu ululà, castello ululì!